There we go! Eventually, Japan prepares for proving the opposite: Not growth-hostile spending cuts, but a growth-friendly spending surge accompanied by expansive monetary policy and a higher inflation target are supposed to help the country out of recession and deflation. It is no wonder that this makes the German Federal Minister of Finance, Wolfgang Schäuble, and the President of the German central bank, Jens Weidmann, shiver, since it shakes their ideology to the very foundations.

That Schäuble is a an economic buffoon has been addressed again and again on this site before. Perhaps it is because his chief economist, Ludger Schuknecht, is otherwise engaged with the production of papers and their pre-publication in German newspapers. Papers on or better against a so called “comprehensive cover mentality“, desperately questioning the financial feasibility of the welfare state, but actually only following the arduous task to wrap an inhumane ideology in a scientific cloak. A cloak so sheer that it is finally only bothering the reader who is on the ball, guess this chap is payed by our taxes, living on the state he treats with hostility. And, of course, it is annoying, too, that there are journalists so fond of a close relationship to politicians and their ministries that they don´t mind to uncritically celebrate such pre-publications.

If such a cerebral tragedy takes place, there is someone who must not be absent. Hear! Hear! It is Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann.

Weidmann said on Monday: “Until now, the international monetary system has come through the crisis without a race to devaluation, and I really hope that it stays that way.”

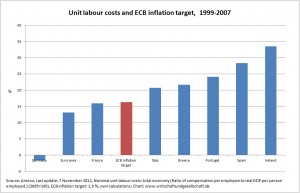

As always, I am meanwhile inclined to say, Weidmann is wrong. To realize his mistake he only had to step out of his front door and look at it from an external view. I suppose, apart from Weidmann and his German followers any economist regardless of the economic school he worships would agree: Germany has already pushed “a race to devaluation” in “the international monetary system” of the Euro area since its very beginning. Inside a monetary union (real) devaluation is about wages falling behind productivity or, more precisely, about wages not increasing in line with productivity to such an extent that the contractually agreed inflation target is to be realized. The economic indicator which measures this and determines inflation are nominal unit labour costs (ULC). Because of the pressure on wages in Germany due to the introduction of a new labour legislation called Agenda 2010 roughly a decade ago annual growth of ULC has been markedly below two percent, the approximate inflation target (“below, but close to, 2%”) of the European central bank (ECB). Gains in productivity, by contrast, have been far from outstanding.

Facing the consequential real devaluation of Germany against its trading partners in the Euro area even the conservative OECD wrote in its Economic Outlook of November 2012:

“A 23 % increase in unit labour costs relative to the rest of the euro area would be needed in Germany to restore 1998 relative competitiveness levels, for instance. If rebalancing takes place only in the countries under financial market stress, the costs would be very high as downward adjustments to relative wages and prices in these countries are currently occurring through economic weakness and high unemployment.”

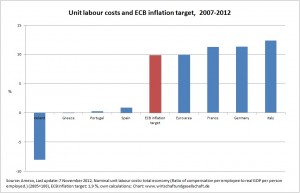

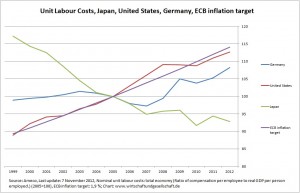

Thus, wages in Germany should vastly increase in relation to productivity. However, the German government persistently refuses to address this problem. Instead, they rather force the countries in crisis to follow their policy. As a consequence, those countries in crisis desperately cut their spending and wages. The “race to devaluation” is already in full swing. And Germany got the ball rolling. This is clearly shown in the two charts below; the first chart shows the development of ULC during the period of 1999 to 2007, e.g. before crisis; the second chart shows the development during 2007 to 2012 since the outbreak of the crisis.

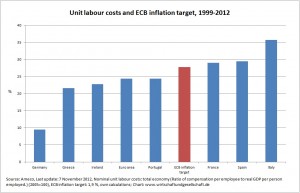

Thus, adjustment takes place but it is onesided and it has not restored yet 1999 relative competitiveness levels. This is shown in the chart below illustrating the whole period from 1999 to 2012. Moreover, the chart indicates that as a consequence of the onesided adjustment process now other countries undercut the ECB inflation target. Therefore, countries still in line with inflation close to two per cent are under growing competitive pressure. The problem of competitiveness is not only far from being solved, it is shifted to the disadvantage of those countries still complying with the contractually agreed inflation target.

The consequences of a downward spiral in ULC are shown by Japan. For years now, Japan has vainly tried to escape deflation.

Now the Japanese central bank has set a two per cent inflation target – close to that of the ECB; it has announced unlimited asset purchases, too. The new Japanese government will try to push economic growth by massive government spending to help the country out of recession and deflation.

The German government should welcome these steps instead of refusing them. If the German government would move in a similar direction it would certainly help to overcome the recession in the Euro area and to revive the world economy, too. It is unclear how long Germany can abdicate responsibility. This will certainly depend on how long the G-20 and the countries in crisis are willing to put up with this.

How outrageous Weidmann and his fellows are is ironically shown by their own data. As Brian Blackstone has put it under the headline “Bundesbank head cautions Japan” in The Wallstreet Journal:

“It is rare for central bankers, including Mr. Weidmann, to criticize the monetary policies of other countries. Monday’s warning to Japan was the German banker’s most explicit to date.

Bundesbank officials worry that, because of Japan’s economic might, the Bank of Japan’s policies could have a signaling effect to other central banks, particularly if they are successful at weakening the yen and boosting exports.”

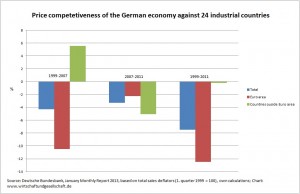

But if you look into the recent January Monthly Report 2013 of the Bundesbank you realize again who is the culprit. On the basis of statistics from the German central bank based on total sales deflators (1. quarter 1999 =100) Germany´s price competitiveness against 24 industrial countries inside and ouside the Euro area has improved during the period 1999 to 2011. Data for 2012 is not yet available. The negative bars in the diagram signal a real devaluation of Germany against the 24 industrial trading partners. And it is interesting to see, that devaluation against countries outside the Euro area has taken off in the period after the outbreak of the financial and Euro crises. Honi soit qui mal y pense.

Price competetiveness of the German economy against 24 industrial countries (click to enlarge chart)

—

Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft – Analyse und Meinung (Economy and Society – Analysis and Opinion) has a as well and is happy if you “follow” or “like” us.

We would be happy, too, if you would like to financially support us through a one time gift or by voluntary subscription. You can do so by simply sending your contribution to:

Account holder: Florian Mahler

Banking house: INGDiBa

Bank Account Number: 5400653788

Bank Code Number: 500 105 17

Reason for Payment: wirtschaftundgesellschaft.de

Dieser Text ist mir etwas wert

|

|

Alltag im Regierungsviertel

Alltag im Regierungsviertel